Robots could help Mauritius clean up devastating oil spill

Robots could be helpful in cleaning up the oil spill that has devastated the coastline of the tiny Indian Ocean island of Mauritius. (See video below.)

Popular with tourists from around the world, the paradise island has been overwhelmed by the oil spill from the merchant vessel Wakashio, operated by Japanese company Mitsui OSK Lines (MOL), and owned by the Nagashiki Shipping Company.

Akihiko Ono, vice president of MOL, has issued an apology for the disaster and says the company is taking the accident “very seriously”, according to The Asahi Shimbun.

More than 1,000 tons of heavy oil for fuel are said to have leaked into the otherwise pristine waters of the Mauritius, and local residents and authorities have called for “urgent international help to stop the ecological and economic damage”, reports the Guardian.

And the stricken ship still looks likely to cause even more damage, according to the prime minister of Mauritius, Pravind Jugnauth, who says: “The risk of the boat breaking in half still exists.”

Thousands of volunteers who have reportedly ignored official orders to stay away have been getting into the water and positioning barriers made of straw to try and contain the oil. Many are risking their health and possibly their lives as they become covered in head to toe with thick black oil.

The current conventional methods for cleaning up an oil spill, as listed on MarineInsight.com, include:

- using oil booms – the floating barrier to contain the spill on the surface;

- using skimmers – a type of small ship or boat or anything that uses sponges and oil-absorbent ropes;

- using sorbents – a type of molecule that absorbs the oil;

- burning the oil where it is, in the water or on the beach;

- using dispersants;

- hot water and high-pressure washing;

- using manual labour – which seems to be the main method in Mauritius;

- bioremediation – referring to creating a mini-ecosystem amid the oil spill to help nature clean itself;

- chemical stablization of oil by elastomizers or elastomers, a polymer that an be used to attract oil; and

- leave nature to sort itself out.

Not included on such lists at the moment, but perhaps will be in the future, are robotic systems.

Robotic systems that can help in oil spill cleanup do exist, and one or two have been tested, but they are still at the research and development stage and not yet commercialized.

In any case, there is probably is no co-ordinated global system for quickly responding with robots to oil spills, possibly because there is no administrative structure for doing so. Having said that, it seems incumbent on the shipping companies or operators of the vessels to ensure they have access to cleanup systems.

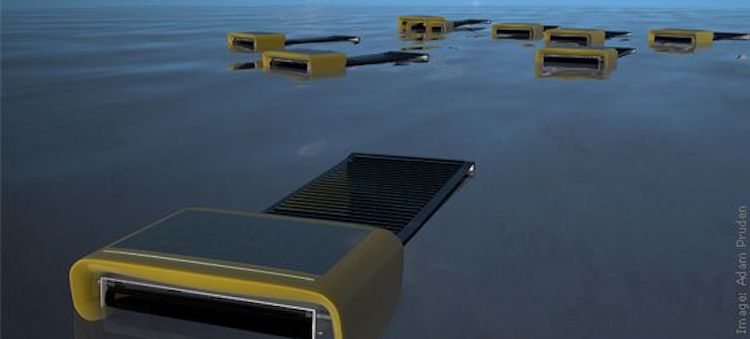

If the shipping industry were to develop such a system based on using robots, one of the solutions they may want to look at is the MIT’s “Seaswarm” robots, first exhibited 10 years ago.

The robots’ inventors estimate that “a fleet of 5,000 Seaswarm robots would be able to clean a spill the size of the Gulf of Mexico in one month”.

The Seaswarm robot is comprised of a head and a conveyor belt covered with a thin nanowire mesh that can absorb up to 20 times its own weight in oil while repelling water.

Sixteen feet long and seven feet wide, the robot uses solar panels for self-propulsion. Seaswarm’s makers claim that, with just 100 watts, the equivalent of one household light bulb, it could potentially clean continuously for weeks.

The vehicle works like a rolling carpet riding over the waves. Stretched across rollers, the belt propels the unit through the water while skimming its surface, then cycles through the vehicle’s head where the oil is heated to separate it from the mesh. The belt then rotates back into the water to collect more oil.

In one design, the robots would burn the oil on the spot so they can continue working uninterrupted. Another design would have the robots occasionally break away to deposit their oil in large floating reservoirs from which tankers could collect it later for reuse.

Intended to work as a fleet or “swarm” of vehicles, the robots would coordinate their work through GPS and WiFi, creating an organized system for collection that can work continuously without human support.

When deployed, the group would find the outer edges of an oil spill and work its way into the center, coordinating the cleanup with minimal human interference.

Thousands of such devices could quickly form “teams” to tackle a spill and because they are smaller than current ocean-skimming technologies, they could navigate hard to reach places like estuaries and coastlines.

Because the oil is processed locally the robots don’t need to make repeated trips back to shore for maintenance, as do traditional skimmers.

And the scientists says: “Because the conveyor belt is so stable – it adheres to the surface of the water, so it cannot capsize – the robot can work under extreme conditions and rough weather.

“Traditional oil skimmers, attached to large boats, are hampered by severe weather. They also require an enormous amount of equipment and human coordination.”

Produced in large numbers, each Seaswarm unit could cost about $20,000.

Other systems at the R&D stage include one being researched by a group of Indian scientists who say that their paper presents “a novel concept for effective oil spill confrontation which is based on autonomous robotic systems using nanotechnology-based techniques”.

Another organisation looking into the issue is the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, or MBARI, which two years ago demonstrated its “long-range autonomous underwater vehicles” for detecting and tracking oil spills.

Although the MBARI robots are not directly capable of cleaning up oil spills, just tracking them, they can be customized to communicate with the robots such as the Seaswarm.

According to the US Department of Energy, approximately 5 million liters of petroleum are spilled into US waters from vessels and pipelines in a typical year.

And although globally the number of oil spills have gone down dramatically over the past few decades to a point where they are a relative rarity, this will be of no comfort to the people of Mauritius, many of whose livelihoods depend on fishing and tourism, both of which have been virtually destroyed in a matter of minutes by the oil spill.

Main picture courtesy of The Bakersfield Californian