Special feature: Tour of Airbus’ advanced manufacturing facility in Germany

Airbus is in the midst of revolutionary changes that may lead the aerospace giant to spend more than $1 billion on robotics, automation and digitalisation technologies across its global operation in the next few years – that’s if the advances at the company’s Hamburg, Germany facility are duplicated in all its facilities worldwide.

The multinational consortium could end up spending a lot more: for example, the final stages of its internal assembly is labour-intensive, with all equipment – seats and luggage compartments – installed by humans. If this stage is roboticised, as the company’s chief operating officer has suggested, it would fundamentally change the current production process, something which he is envisaging anyway.

Robotic technologies have already transformed the way Airbus manufactures the exterior shell of its planes. Whereas, in the past, human workers would have drilled the 6,000 or more external holes in the fuselage of a typical commercial airliner, now, robots not only drill them, they also rivet or fasten them.

Perhaps surprisingly to some readers, the drilling was done by humans all these years until now, and even now, it’s only at the Hamburg facility that robots have been brought in.

Last week, Airbus provided more insight into its highly automated aircraft manufacturing facility in Hamburg – a place called Finkenwerder, to be precise, at what’s described as a “private airport”.

The aerospace jumbo invited a small group of journalists, including one from Robotics and Automation News, for a visit to the vast, sprawling complex, and a detailed, guided tour of Hangar 245, the advanced manufacturing facility in which aircraft belonging to the “A320 Family”, as Airbus describes them, are currently being assembled.

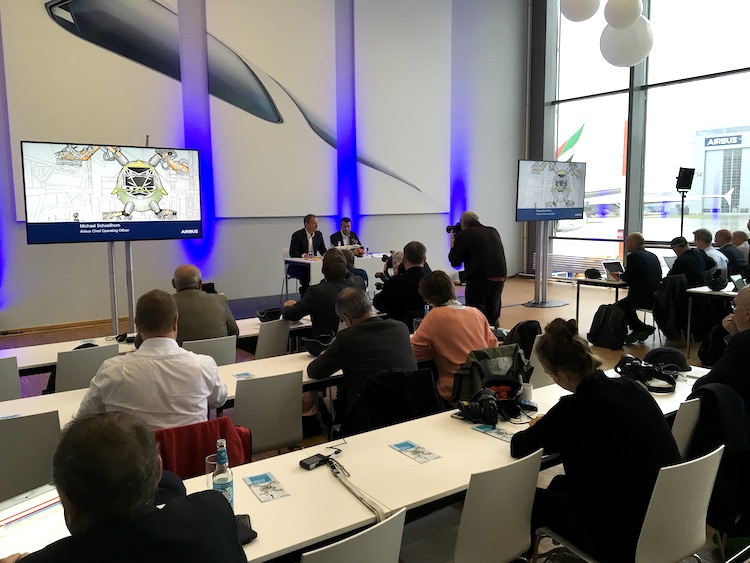

The day began with a press conference, presented by two of the company’s senior executives:

- Michael Schoellhorn, chief operating officer and member of the Airbus executive committee (pictured below, seated left); and

- André Walter, head of the Hamburg plant and industrial site and deputy chairman of the board of management of Airbus operations (pictured below, seated right).

(Watch out for extended comments from the two executives in a future article.)

From challenger to leader

Airbus was founded in 1970 by France, Germany, Spain and the Netherlands as a challenger to Boeing, the American aerospace company, which virtually monopolised the market at the time.

Now, both Boeing and Airbus hold about 90 per cent of the global aerospace market, effectively making the sector a duopoly. Airbus has annual revenues in the region of $65 billion, while Boeing $100 billion.

With such large, complex multinational corporations, it’s difficult to glean much detail from headline figures like that, but certainly the two companies are the pre-eminent companies in the aerospace sector.

Other countries, such as China and Russia, do produce commercial planes and try to grow their market share, but Airbus and Boeing have a long history and advanced technology which appear to be serving as insurmountable barriers to entry for would-be competitor countries and companies.

Having said that, there are numerous manufacturers of smaller aircraft, such as Honda, Gulfstream, Embraer and so on. Then there are also companies in the space sector which come into competition with Airbus and Boeing.

But with 45 per cent each of the commercial aircraft market, Boeing and Airbus are in commanding positions, even though Boeing has had a few problems stemming from the crashes of its 737 planes.

Boeing’s troubles are likely to be temporary, and people at Airbus say they are expecting to see the iconic US industrial company make a strong return to the market.

In fact, when it comes to implementing robotics and digital technologies, Airbus executives accept that Boeing is perhaps a couple of years ahead.

Asked if Boeing’s manufacturing process was more advanced, Schoellhorn said: “I wish I knew. We know that Boeing is also very active on their manufacturing system.

“But I think in terms of some of the things we’re doing – our digital manufacturing system – they probably started a couple of years prior. I don’t know precisely, but typically it’s a head-to-head race.”

Around the world in one company

Airbus is a massive aerospace company with too many business activities to cover in one article. But in the commercial aviation segment, its main product is its A300 planes.

The full range includes the A318, A319, A319neo, A320, A320neo, A321 and A321neo as well as the A321LR and A321XLR.

Orders are increasing and the company will have to ramp up production, and a “significant increase in automation” is seen as the way to achieve this. Preliminary estimates suggest that production has increased approximately 20 per cent through the use of robotics.

Schoellhorn said: “With the rate increase of the past years, the current rates and future rates, we need more automation and more effective production.”

The company has offices and production sites all over the world, from Europe to the Americas and China. In Europe, its largest facilities are in Germany, the UK, France and Spain. In the US, its largest facility is in Mobile, Alabama, but it also has facilities in Wichita, Kansas, and Herndon and Ashburn, Virginia, among others. In China, it has a facility in Tianjin, south-east of Beijing, for final assembly – which means seats, overhead luggage compartments and other internal fittings.

Hamburg is the largest Airbus site in Germany, and employs more than 13,000 people. It is at this facility that structural assembly and equipping of fuselage sections take place.

The Hamburg site also serves as the logistics hub for Airbus’ final assembly lines outside Europe – Tianjin, in China, and Mobile, Alabama, in the US. All major aircraft components are collected and shipped from Hamburg.

Moreover, Hamburg-Finkenwerder also contains the A380 major component assembly hall, which houses the structural assembly and the equipping of the forward and complete rear fuselage sections.

These fully assembled and equipped fuselage sections are produced here and then shipped to the A380 Final Assembly Line in Toulouse, France on a specially-built roll-on, roll-off sea ship.

Close to the commercial airport of Hamburg-Fuhlsbüttel, Airbus operates a large spares centre – which holds some 120,000 proprietary parts, as well as a 24/7 spares call centre for its customers from around the world.

Hangar 245, which is the facility we visited, is said to be the most advanced in terms of robotics and digital technologies. Successful processes here will be copy-pasted into other Airbus facilities worldwide.

Walter said: “Hangar 245 shows the future. It’s the most advanced structural assembly line in the whole company of Airbus.”

The belly of an aeroplane

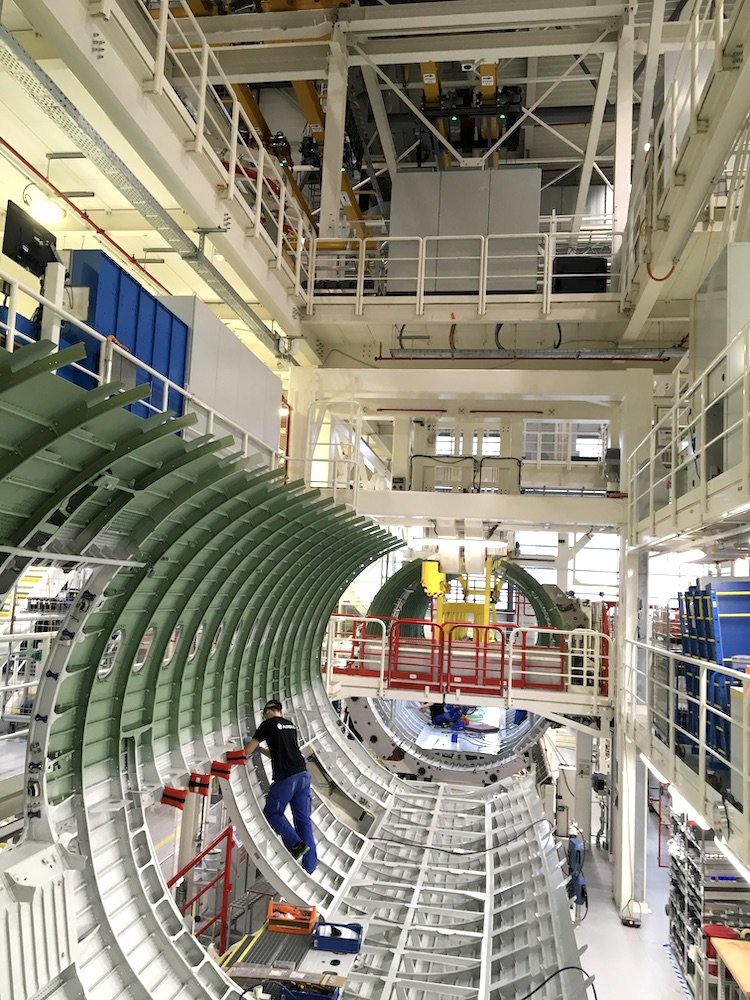

Hangar 245 is a huge facility over three floors, although it’s easy to overlook the sheer amount of space because of the massive aeroplane parts being worked on inside.

Airbus has been using what might be termed a “traditional” workshop approach to assembly since its inception, and you can see that in the layout.

And while I might have imagined many people working there, there were actually just one or two people – maximum three or four – at work in each section.

It might be surprising to some – myself included – that robots are a relatively new addition to the aircraft manufacturing sector, especially when you consider that the automotive sector has been relying on robots for many decades now. In fact, the vast majority of work in aircraft fuselage production has been done by human workers.

Until now. And Hangar 245 is a sign of things to come.

For Schoellhorn, who has a background in the automotive industry, it’s an essential development: “In order to stay competitive, we need to make that transition to more automation.

“Definitely we look at automotive and the high degree of automation that has been mastered in automotive.

“But I would say, having been in both industries, what we do is more difficult, in that the design of the single-aisle (aircraft) is not as mature, not as digital as automotive designs are today.”

Flextrack to the rescue

Imagine having to drill 6,800 holes into the steel fuselage of an Airbus plane – that’s how many exterior holes are needed for each plane. Not easy. Even if the material has changed to carbon-fibre and composites, that’s still a lot of drilling to do by hand.

So, Airbus has invested in technologies such as the Flextrack robot, made by a US company called MTM Robotics.

Airbus describes Flextrack as a “modular, lightweight automated system”.

Eight Flextrack robots do the drilling and counter-sinking of 1,100 to 2,400 holes per longitudinal joint.

In the next production step, 12 robots, each operating on seven axes, combine the centre and aft fuselage sections with the tail to form one major component, drilling, counter-sinking, sealing and inserting 3,000 rivets per orbital joint.

The figure 6,800 is probably an underestimation. Certainly if the internal work is included, there are many more thousands of drill holes required. And that’s before we talk about the joining or fastening work required.

Walter said: “A total of 20 robots for drilling, dropping, and positioning of rivets to reduce lead time is implemented in this hangar.

“Automated positioning of sections with 0.2 mm accuracy using laser measurement systems are implemented in all lines.”

Schoellhorn is already looking ahead to possibly changing how the internal work is done. “I think we also need to think of automating more structural and the interior equipping,” he said.

“Today, we do most things from the outside, we put the pieces together. But we do a lot of things inside (the plane) that today is very manual, partly also heavy – people carrying relatively heavy loads.

“These are things we need to look into.”

This is a job for a Titan

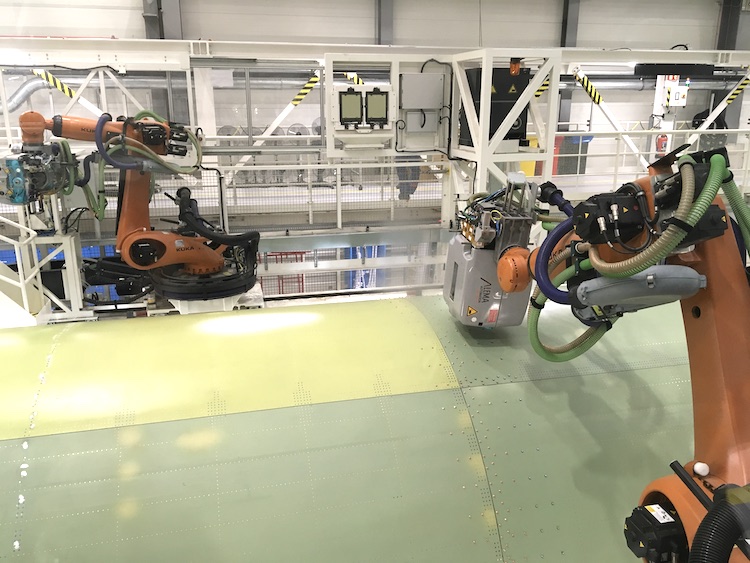

While the Flextrack robot is used for individual parts – or sheets – of the fuselage, giant Kuka robots are put to work on semi-assembled fuselages, as shown in the above picture.

These are the Kuka’s biggest robots, the “Titan”, and they are caged off, or at least positioned behind a clear screen. The end-effectors – the grey boxes – are produced and supplied by Alema Automation, a company which Kuka acquired about five years ago. Kuka has a dedicated aerospace division called Kuka Systems Aerospace.

So the Kuka robot does the positioning and the Alema end-effector does the drilling and fastening.

According to a study by Hamburg University, Airbus may be saving approximately 50 per cent of the recurring cost and workload by using this new robotic system.

That’s probably another underestimate. Just imagine having to manually drill and fasten 6,800 holes into a plane fuselage.

Melissa Ferrara, one of the workers at the facility, said: “While the robot is doing this work, you can do other work – production can go faster.”

She adds that it’s a case of learning on the job, even after the formal training provided by Airbus. “We just have to get experience. The real training is direct experience – you just have to use it every day.”

What Ferrara and her colleagues learn at Hangar 245 will be transferred to other Airbus factories worldwide, although the company does have some old production facilities where it may not be viable or even possible.

Schoellhorn said: “To what degree we go backwards is not yet decided. We will still have some legacy lines that we might probably leave as they are because they just don’t have the basis to be fully automated.”

Learning curve

Schoellhorn also described what sounds like a fundamentally new way of designing and making aircraft which could become the standard way of doing things in every manufacturing enterprise.

Schoellhorn said: “We need to design the production system at the same time as we design the product. In the past, that has been done sequentially.

“The product designers were the heroes, and the rest (of the work) was about executing what was put on a 2D plane. Now, today, going forward, we need to do it differently.

“We need to have the product designer, the manufacturing system designer, and the supplier around the table (at the same time), to bring all their experience and wisdom to the solutions so that it is about the designers and also about manufacturability.”

And although he said “table”, what he probably means is a digital method for collaboration, another area which Airbus has been heavily invested in.

The interesting thing about the learning curve Airbus is on is that so much of it is new and no one else has done it before. Yes, the automotive and other sectors may provide some valuable insights, but given that Airbus is now the leading commercial aircraft manufacturer in the world, it will have to find its own way forward.

So Hangar 245 is not only a fully operational production facility, it is also an innovation centre, complete with a section which studies and trains workers in areas such as collaborative robotics and virtual and augmented reality (pictured above).

Walter calls this the “learning and exploration” aspect of Airbus’ digital and automation journey.

“Since we started from scratch with this hangar, we have had the chance to think and rethink the process and the layout of the workstations,” he said.

“So our objective was to optimise the production, to reduce the workload for our employees, and to shorten the lead time.”

Digitalisation and artificial intelligence

Although we haven’t delved into the computing side of the operation in this feature, it’s certainly a vast and interesting topic. (There’s only so much you can do with one article.)

According to Schoellhorn, all of the digital processes at Airbus are being integrated into one system and artificial intelligence is used throughout the process to optimise everything. This is a trend that is likely to continue and grow, since AI itself is going through a variety of changes and developing all the time.

Schoellhorn said the company is aiming for “digital continuity” across its entire operation.

“The PDM (product data management), the ERP (enterprise resource planning), and MES (manufacturing execution system) all use digital data as inputs,” he said.

“The robots are all connected, the sensors are all connected, all the data is captured, and we have an AI-reinforced backbone system.”

I found it interesting to see so few human workers inside such a large facility. And while it’s unlikely that they too will disappear in time and Hangar 245 will become a fully automated facility with AI running the entire place, it’s probably safe to say it’s a cyber-physical system, where humans and machines are working together – and that description is likely to only become more apt.

The process of Airbus’ transformation will be interesting to see over the next few years, and we at Robotics and Automation News feel fortunate to be seeing it all close up.