Watchmaking robots: It’s a small world

When Apple wanted to launch a watch, most people may have thought the company would name it iWatch, to go with iPhone, iPad and iLife.

However, Swatch raised a legal objection on the grounds that it had the rights to a product called iSwatch, and Apple’s iWatch would be too similar. This week, the courts agreed and banned Apple from using the name.

But Apple had already changed its mind some time ago, and went with Apple Watch, which has gone on to sell 13 million units in its first year, estimated to be a faster sales rate than the iPhone.

But as a total, 13 million is barely a drop in the ocean of the global watch market.

According to SatisticBrain.com, 1.2 billion watches are sold annually worldwide. Of those, around 77 per cent are mechanical, and the rest are electronic.

Before the electronic watch era, Switzerland virtually owned the global market for timepieces. Swiss watches and clocks were probably the most ubiquitous mechanical device on Earth, and they were all mini-masterpieces of intricate assembly of many tiny components.

Then in 1960s, quartz technology was invented.

Winding down the old world

Quartz is a battery-driven electronic system which the Swiss shunned because making mechanical watches had become bound up with national identity and pride. But quartz was embraced by the Japanese, in particular by Seiko and Citizen, partly because quartz can make the battery last several years.

And as inexpensive quartz timepieces became more and more popular globally, the Swiss watchmaking industry came under more and more pressure. Employment in the sector fell from nearly 100,000 to around 30,000 in the 20 years starting in 1970.

The Swiss, then, were faced with losing the watchmaking business entirely or adapting to the new, non-mechanical world. The choice was obvious: adapt.

Swatch was the signal that Swiss watchmakers were willing to compete globally using new technology.

Established in 1983, Swatch was a collaboration between leading Swiss watchmakers, and their plan was to regain market share lost to the Japanese and at the same time maintain the prestige of Swiss watchmaking.

Now, a couple of decades later, a quick look at the pie chart using data from StatisticBrain.com shows Swatch as the world’s largest watch manufacturer.

[visualizer id=”7456″]

Richemont, which takes second place, and Rolex, in third, are both Swiss watchmakers. Together, the top three watchmakers – all Swiss – have around 40 per cent of the global market. Add to that the other Swiss watchmakers further down the order, and it seems Switzerland is still the world’s watchmaker.

And if you think greater use of robots might give other countries and companies a competitive edge, Swatch is already on the case. In recent years the company has embraced robotics in a big way.

Robots wearing watches

Robotics in watchmaking is at least 30 years old, having been pioneered by Seiko Epson on its production lines in the early 1980s.

Seiko’s classic advertising slogan – “Some day, all watches will be made this way” – can be better understood with their production processes in mind.

In fact, Epson Robots as a company, or business unit at least, was established as a result of the parent company’s successful development of assembly robots for watchmaking.

The video above provides a glimpse into Epson’s early watch production processes, subsequently adopted by Swatch, which has gone even further by launching a range of watches designed specifically for robotic assembly.

The Swatch Sistem51 is a mechanical watch made of 51 parts – half as many components as a conventional mechanical watch, and is assembled entirely by robots.

Speaking last year to the Swiss Broadcasting Corporation, Pierre-André Bühler, of the Swatch management board, says: “The concept for this product was completely new. We started with a blank sheet and wanted to produce a mechanical watch for 150 francs ($155).

“The biggest challenge was to do this using a fully automatic production system. This is a world premiere. Nothing like this has ever been done before.

“Before, we worked with 55 different machines. Now, with our five high-tech production lines, we can manage with a minimum number of employees, whose job it is to assist the robots, take charge of production and develop software, so we can reduce production times enormously.”

Given that these days, a high-end mechanical watch can set you back thousands of dollars at least, a high-quality mechanical watch made by the Swiss for around a couple of hundred dollars seems a bargain.

Good, clean fun

Watches, like many electronics products, are manufactured in dust-free environments, or “cleanrooms” as they are called.

Robots used in cleanrooms are required to have the appropriate classifications, such as the cleanroom classification acquired by Universal Robots for its machines.

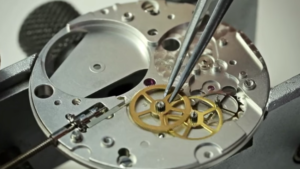

But while many robots from all the major robot manufacturers have cleanroom classifications, not all of them have the necessary grippers and extensions for use in watchmaking, which uses parts so small they can hardly be seen with the human eye, requiring the use of magnifying glasses and tweezers to handle.

When put together, the position, proximity and movement of watch components can be measured in nanometres. Perfect job for a robot, but only the big companies have so far developed the necessary peripherals and systems to work in such small worlds.

But with so many smaller-scale makers of electronics gadgets, it’s probably only a matter of time before such peripherals become more widely available.

Manipulation on the microscopic scale

The need to work in such small spaces with tiny components has opened up a new field of robotics, one concerned with something called “micromanipulation”.

A couple of years ago, a company called Percipio launched its Chronogrip robot (pictured), which can manipulate and assemble high-precision mechanical parts ranging from a few millimetres to a few thousandths of millimetres in size.

The Chronogrip cannot operate on its own and requires a human, which makes it possibly the first collaborative robot, or at least a very early example.

As Precipio’s CEO, David Heriban, tells Atelier.net: “A robot isn’t intelligent enough to understand what is happening at micro-world scale, so it needs a person, but the person needs the robot to manipulate objects with high levels of precision at this scale.

“The idea behind Chronogrip is to be extremely precise, to help the person concerned to assemble the components.”

A customisable future

A key advantage of the Chronogrip is that it is versatile enough to be used for making watches or chipsets.

In fact, this is the key advantage of collaborative robots in general, which is probably why there is so much interest in them.

For decades, industrial robots have been hulking great masses of metal used in big manufacturing, and that will continue to be the way it is for a long time to come.

Collaborative robots still only represent less than 5 per cent of the total global industrial robot population.

But given that they are relatively affordable, a craftsman – say, a watchmaker – could invest in one and find his work is aided by it. And if that catches on, we could see a return to an age when millions of products were tailored to individual customers’ specific requirements instead of almost everything being mass-manufactured as it is now.