As 2026 rumbles into life, the humanoid robotics field has generated fresh headlines that underscore both the accelerating pace of innovation and the widening range of actors entering the race.

In Shanghai, robotics startup DroidUp unveiled Moya, billed as the world’s first biomimetic embodied intelligent robot, capable of walking with near-human gait, showing micro-expressions, and maintaining warm skin designed to support more natural interactions with people.

At the same time, a growing wave of Chinese industrial groups – including major automakers and tech conglomerates – has signalled their entry into humanoid robotics, expanding the field from research prototypes to platforms aimed at commercial use cases.

These developments arrive amid continued debates over the commercial timelines for Western projects such as Tesla’s Optimus humanoid.

While Tesla continues to talk up Optimus and third-generation units, broad availability remains years away, raising questions about whether the company is scaling back ambitions or simply pacing development.

1. Why humanoids – and why it matters now

Humanoid robots have long been a staple of robotics research: the ideal physical form for operating in environments built for people, from factories to offices to living spaces.

Advances in AI – from embodied perception systems to adaptive motion planning – have reinvigorated interest, giving engineers new tools to tackle historically hard problems like balance, manipulation, and human-robot interaction.

But this signal in funding and attention also reflects broader macro trends: labour shortages in logistics and manufacturing, ageing populations in developed economies, and a premium on flexible automation that can adapt to diverse tasks.

In 2026, humanoids are less about abstract futurism and more about whether they can find real work in real environments.

2. The core technologies driving progress

At a technical level, modern humanoid platforms are defined by progress – and constraints – across several domains.

- Mobility and balance: Dynamic walking and balance have improved dramatically from the slow, staticky bipedal gaits of a decade ago. But robust locomotion over uneven environments and reactive recovery without falls remains challenging outside controlled settings.

- Manipulation: Hands and arms capable of dexterous interaction with real-world objects continue to lag human capability. This is one of the largest gaps between research achievement and commercial utility.

- AI and cognition: Recent work in embodied AI – integrating perception, planning, language understanding, and action – is perhaps the most significant shift. Models that can reason about a scene and adapt behaviour in real time are now central to competitive platforms.

- Power and endurance: Batteries and actuators still limit operational time and strength; many humanoid designs trade off energy efficiency for capabilities.

Together, these layers make for platforms that are impressively capable in demos and narrow tasks, but far from general-purpose autonomy.

3. Pilots and early real-world tests

While mainstream commercial adoption remains nascent, several humanoid systems are entering pilot deployments:

- Automotive and industrial environments are experimenting with humanoids to assist in inspection and material handling.

- Service and hospitality sectors are piloting robots for dynamic interaction roles.

- Research labs and universities continue to push the state of the art in controlled environments.

Importantly, many of these are early co-pilot or supervised applications, where the robot augments human operators rather than replaces them entirely.

4. Platform roundup: Who’s leading the race?

Humanoid robotics today is not a two-horse race. Instead, platforms vary by ambition, capability, and commercial strategy.

Industrial-scale ambition

- Tesla Optimus: Still the headline project in the West, Optimus aims to bring general-purpose humanoids to scale. Production timelines have shifted repeatedly, but development continues with an eye toward both internal factory use and external customers.

- Figure Robotics: Focused on highly capable humanoid systems with robust motion and AI stacks designed for industrial partners and research applications.

- Apptronik Apollo: Positioned as an engineering-first platform, marrying robust hardware with modular autonomy.

Advanced engineering leaders

- Boston Dynamics Atlas: Long a showcase for humanoid mobility research, today Atlas serves as both a technology demonstration and a proving ground for advanced locomotion and perception.

- Agility Robotics Digit: Emphasises reliable bipedal motion and payload handling for logistics environments.

Chinese and Asia-based challengers

A rapidly growing cadre of companies is emerging from China, often backed by automotive and technology conglomerates. These firms leverage deep manufacturing ecosystems to iterate quickly and pursue real-world use cases:

- DroidUp’s Moya: Claims of biomimetic embodiment and human-like interaction represent a different axis of focus from pure industrial utility.

- A growing and already-large list of other players, including firms expanding from automotive and AI backgrounds, are testing humanoid platforms with varying design emphases and application targets.

This regional diversification matters because it broadens the competitive set and invites multiple approaches to solving foundational problems.

5. Economics and commercial viability

Humanoid robots are expensive to build and maintain. Until unit costs fall and reliability improves, their value proposition must be framed in terms of total cost of operation rather than headline sticker prices.

For specific industries – logistics, warehousing, assembly – the argument can be made if robots deliver reliable uptime and task flexibility.

But for broader, general-purpose use, the economics are still unresolved: training, safety validation, and service infrastructure add costs that typical industrial robots do not require.

6. The capability gap: Autonomy vs supervision

Most current systems perform best in structured or semi-structured settings with some level of supervision or teleoperation. Fully autonomous, general-purpose behaviour – the humanoid equivalent of true field deployment – is still out of reach. Key challenges include:

- Task variability

- Unexpected obstacles

- Real-time sensor processing

- Safe human interaction

These aren’t hurdles that any single company has fully solved yet, and progress will require both incremental engineering and systemic innovation.

7. Competition and strategic priorities

The global humanoid landscape reflects varied strategic priorities. Western projects often emphasise AI-driven autonomy and integrated software stacks. Asian players frequently combine advanced hardware with rapid iteration cycles powered by manufacturing scale.

This competitive dynamic could ultimately accelerate progress, but it also highlights divergent paths: some aim for high-capability generalists, others for targeted task executives.

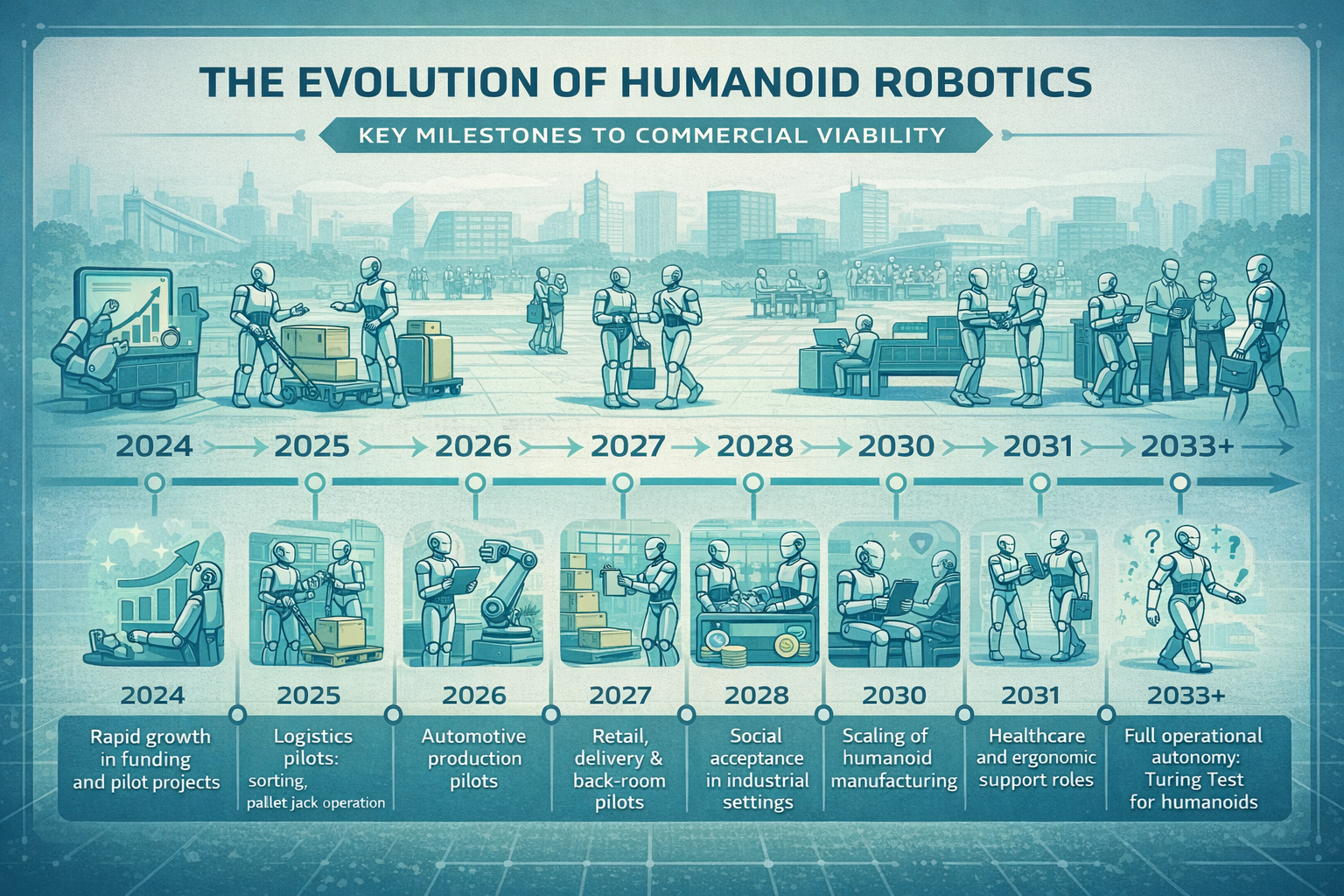

8. Looking ahead: Milestones and expectations

Predicting when humanoid robots will cross specific capability thresholds is inherently speculative, but a plausible trajectory might include:

- 2026-2028: Broader industrial pilots with semi-autonomous task execution

- 2028-2032: Early commercial deployments in logistics, warehousing, and specialised service roles

- 2030s: Increasing autonomy and multi-functional humanoids capable of unstructured environment tasks

A “Turing Test”-like milestone for humanoids – reliable, unsupervised operation in unpredictable environments, and capable of a variety of tasks that humans can complete with ease – remains a long-term objective rather than an imminent reality.

9. Social acceptance and workforce implications

Even as technology advances, acceptance by workers, customers, and regulators will shape adoption. Humans tend to judge humanoids not just on utility but on safety, predictability, and social comfort.

Humanoid robots may augment workforces rather than displace them outright in many sectors, particularly where human judgement and social interaction are essential.

10. Humanoids – not imaginary, not imminent

Humanoid robotics in 2026 is a field in transition: the technology has moved beyond curiosities to platforms that can do things, but the leap to ubiquitous, reliable, general-purpose robots is still ahead.

Progress will come not from a single breakthrough but from a series of incremental advances – in perception, power, manipulation, and autonomy – each stitched together with robust engineering.

In the years ahead, the question isn’t if humanoid robots will matter – it’s how and where they will first earn their place.