Every year, the world generates tens of millions of tonnes of electronic waste, while periodic semiconductor shortages and supply disruptions have simultaneously left factories scrambling for parts.

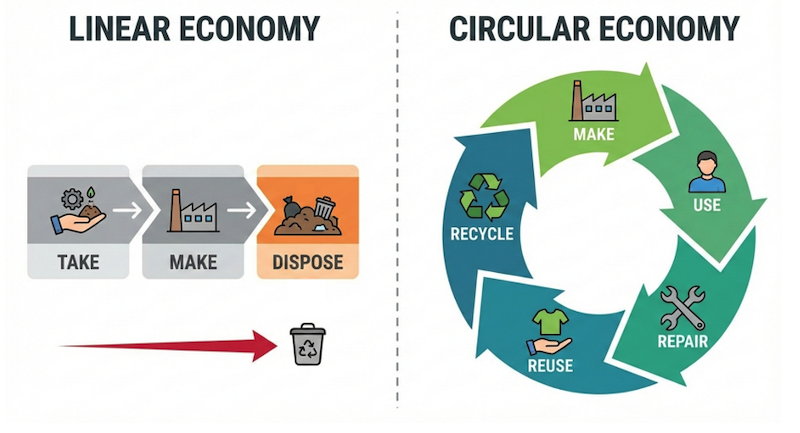

This paradox – excess discarded hardware alongside unmet demand – captures why a circular approach matters. In industrial automation, the circular economy means shifting from a “take-make-dispose” lifecycle to one that restores, reuses and recycles equipment.

Extending the life of PLCs, drives and I/O modules is therefore not only an environmental imperative but a strategic way to strengthen supply-chain resilience and reduce capital outlay during times of component scarcity.

The Business Case for Circularity in Automation

Economic Advantages of Refurbishment

Refurbished units commonly cost 30-50% less than brand-new OEM replacements. For procurement teams, that delta can translate into hundreds of thousands of dollars saved across multiple production lines.

Beyond unit price, circular strategies help avoid “forced upgrades” – replacing an entire machine because a single module is unavailable – which often triggers large capital expenditures and extended downtime.

When evaluated over the asset’s useful life, modest investments in repair and recertification typically deliver much higher return on capital than wholesale replacement.

Reducing Industrial Carbon Footprint

The majority of a component’s embodied carbon is created during manufacturing (mining, wafer fabrication, and assembly), not during its operational phase. Extending a device’s useful life by five years spreads that upfront carbon cost over a longer service period and substantially lowers annualized emissions.

Practical Strategies to Extend Hardware Lifespan

Component Level Repair vs. Replacement

Board-level repairs – replacing electrolytic capacitors, worn connectors, or failed relays – are often more economical and faster than procuring a new module. Modern repair labs perform thermal imaging diagnostics, X-ray inspection and micro-soldering to restore functionality on legacy PCBs.

- Common repairs: capacitor replacement, firmware re-flashing, connector reseating.

- When to repair: when failure is localized and spare subcomponents are available.

- When to replace: when multiple board layers are delaminated or key ICs are irreparably damaged.

Strategic Sourcing from the Secondary Market

A resilient sourcing strategy blends primary OEM channels with vetted secondary suppliers and independent distributors. Not all surplus sellers are equal: verification, traceability, and testing history are essential to avoid counterfeit or degraded stock.

In practice, relying on established partners like Iainventory ensures that “second-hand” does not mean “second-rate”.

Preventive Maintenance and Environment Control

Simple steps reduce failure rates and prolong service life:

- Improve cabinet airflow and cooling to lower component temperatures.

- Install dust filtration and positive-pressure ventilation to reduce contamination.

- Replace volatile memory batteries and RTC cells on schedule.

- Implement periodic burn-in tests for critical spare modules.

Mitigating Risks in the Circular Supply Chain

Quality Assurance and Testing Standards

Buyers should insist on transparent QA protocols: visual inspection, functional load testing, burn-in periods (24-72 hours), and documented test results. A well-executed refurbishment with certificate of test and a short warranty can be more reliable than “new old stock” that has sat unused for a decade without power cycling.

Navigating Obsolescence

Manufacturers publish EOL notices that gradually reduce the availability of spares. A circular supply network helps bridge that gap: repair services, secondary inventories and managed spares strategies allow plants to operate legacy lines long after OEM support ends.

For many operations, accessing a deep inventory of Iainventory obsolete components allows managers to maintain legacy systems long after the OEM has moved on.

FAQ: Circular Economy in Industrial Electronics

Q: Does using refurbished hardware void my system warranty?

A: Not generally. Warranty implications depend on the original equipment contract. Refurbished parts usually carry their own warranty from the refurbisher; confirm contract terms before installation and document any third-party parts used.

Q: Are refurbished parts less reliable than new ones?

A: Not necessarily. Used parts have passed initial “infant mortality” and, when properly tested and recertified, can provide very stable long-term performance. The key variables are the thoroughness of testing and the refurbisher’s processes.

Q: What is the difference between “refurbished” and “used”?

A: “Used” typically means sold as-is with unknown history. “Refurbished” implies an active restoration process: cleaning, inspection, repair or component replacement, functional testing, and often a defined warranty.

Conclusion

The circular economy is a practical evolution for industrial electronics: it reduces environmental impact while strengthening supply-chain resilience and controlling costs.

For sustainability officers and procurement managers, the next step is operational: review scrap and spare policies, prioritize repairable assets, and incorporate trusted secondary suppliers into sourcing strategies.

Manufacturing’s future will not be defined solely by the newest silicon – success will belong to teams that make the smartest, most sustainable use of the hardware already in play.