India is one of the world’s largest and fastest-growing manufacturing economies, but it remains under-automated compared with its rivals.

According to the International Federation of Robotics, India installed just over 8,500 industrial robots in 2023, up 59 percent year on year.

That growth is encouraging, but India’s robot density – about 7 units per 10,000 workers – still lags far behind China (392) and South Korea (1,012).

Yet the potential is obvious. With a population of 1.5 billion, an ambitious “Make in India” strategy, and pressure from global supply-chain diversification, India could become the next major frontier for robotics.

The question is: will the future be defined by foreign robot makers expanding into the country, or by home-grown companies building systems tailored for local realities?

Assimilation incoming

Most of the world’s leading robot manufacturers – ABB, Kuka, Fanuc, Yaskawa, Universal Robots, Omron, and others – already have operations in India. They bring global standards, established product lines, and heavy R&D.

Their presence is reinforced by new infrastructure such as Omron’s recently opened Automation Center in Bengaluru, which provides proof-of-concept facilities, training, and technical support.

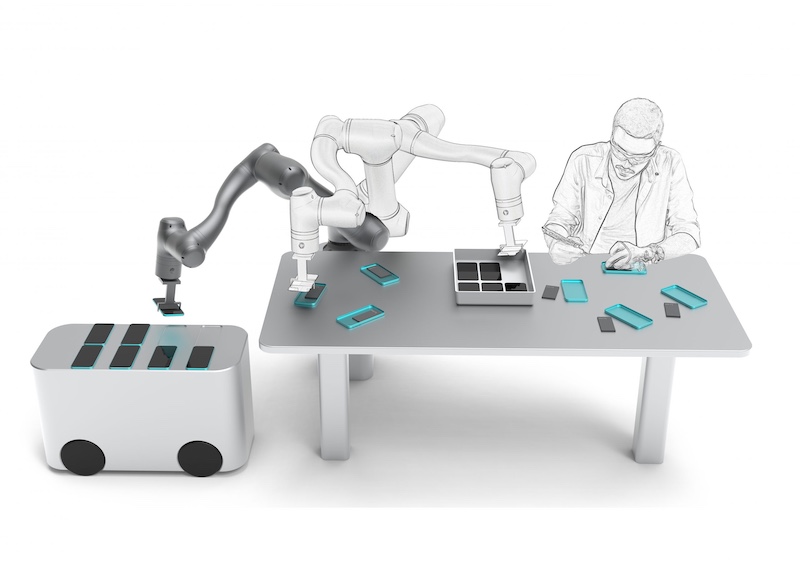

This influx is reshaping expectations among Indian manufacturers. Foreign robots are tried and tested, but they come at premium costs and may not always be suited to India’s fragmented industrial base of small and medium-sized enterprises.

That leaves a gap: machines designed, built, and priced specifically for Indian conditions.

Domestic robotics firms are beginning to fill that gap. They tend to focus on lower-cost, rugged systems, with simplified integration and local service networks. Their challenge is to scale – but their opportunity is massive.

India’s robotics ecosystem: 28 companies to watch

What follows is a list of Indian robotics companies focused on building machines that move – mobile robots, manipulators, drones, inspection crawlers, cobots, and service robots.

The list avoids pure component makers or software-only firms, and instead highlights builders of physical robotic systems.

- Addverb Technologies – Warehouse robotics and automation, backed by Reliance Industries.

- GreyOrange – AI-driven warehouse robots and sortation systems, operating globally.

- Svaya Robotics – Collaborative robots designed and built in India.

- Project Shiva – Prototype robotic systems from the Prototypes for Humanity initiative.

- SS Innovations (SSI) – Custom robotic manipulators and specialized automation.

- Unbox Robotics – Parcel sorting robots for logistics and last-mile delivery.

- Ati Motors – AMRs (Sherpa series) and mobile manipulators for factories.

- Systemantics – Industrial robot arms and cobots for MSMEs.

- Hi-Tech Robotic Systemz – AMRs and autonomous shuttle systems.

- Genrobotics – Sewer-cleaning robots such as “Bandicoot”.

- Sastra Robotics – Robotic test automation systems for electronics and HMIs.

- Planys Technologies – Underwater ROVs for inspection of tanks, ports, and dams.

- IdeaForge – Drones for defence, surveillance, and industrial inspection (IPO in 2023).

- Asteria Aerospace – UAVs for defence and mapping (majority acquired by Reliance Industries).

- Garuda Aerospace – Multi-role drones for agriculture, defence, and disaster relief.

- Omnipresent Robot Tech – Inspection drones and industrial robots for utilities.

- Skylark Drones – Drone operations and data platforms for mining and infrastructure.

- Asimov Robotics – Service and industrial robots for hazardous tasks.

- DiFACTO Robotics & Automation – Integrator and builder of robot welding and finishing systems.

- CynLr (Cybernetics Laboratory) – Vision-based robotics for flexible “pick-anything” tasks.

- Invento Robotics – Service robots including humanoid “Mitra”.

- Gridbots Technologies – Robots for nuclear, space, and pipe inspection.

- Anscer Robotics – AMRs and pallet movers, recently expanded into the US.

- Robosoft Systems – Robots for duct and HVAC inspection and cleaning.

- Grene Robotics (Indrajaal) – Counter-drone robotic defence systems.

- SP Robotic Works – Educational robotics kits and entry-level machines.

- Peer Robotics – Collaborative mobile robots for plant logistics.

- Wipro PARI Robotics – Large-scale industrial automation and robotics integrator.

Together, these companies represent the breadth of India’s robotics ecosystem, spanning warehouse automation, drones, service robots, industrial arms, sanitation systems, and specialized inspection machines.

Big backer

Among the most prominent are GreyOrange and Addverb Technologies, both with global visibility in warehouse robotics. GreyOrange is now a multinational, while Addverb’s tie-up with Reliance Industries – an Indian multinational conglomerate with approximately $120 billion in annual turnover – has given it capital and credibility to scale.

Genrobotics has carved out a social niche with its sewer-cleaning machines, replacing dangerous manual scavenging.

Sastra Robotics and Planys Technologies show how Indian startups can export advanced systems for specialized tasks, from testing electronics to inspecting underwater assets.

IdeaForge and Garuda Aerospace demonstrate the strength of India’s drone industry, which has attracted both defence and commercial interest.

This diversity is important. India’s fragmented industrial base – millions of small and medium sized enterprises and workshops – will not adopt the same automation solutions as large automotive OEMs. Niche players are better placed to serve them with tailored machines.

Four wheels good, two wheels good

Globally, about half of all industrial robots are sold to the automotive sector. India has domestic automakers – Tata, Mahindra, Bajaj Auto, Hero MotoCorp, TVS – and a massive motorcycle market.

But unlike Chinese companies such as BYD or SAIC, Indian manufacturers have not yet emerged as global automotive giants.

One reason is the uneven use of automation. Indian vehicles often serve local demand at lower price points, where tolerance for variation in manufacturing is higher.

Exporting at scale requires consistency, precision, and reliability – qualities best delivered by robotic production lines.

If Indian automakers embrace robotics more aggressively, they could shift from regional players to global exporters.

Organic versus mechanistic

There is still a cultural acceptance of “organic” design in India: hand-finished goods, small variations in mass-produced items, a certain artisanal irregularity. While this may be charming locally, it is incompatible with global markets that demand uniformity.

Robots are, by definition, precise and repeatable. India’s manufacturing future depends on whether it retains its artisanal identity or embraces industrial accuracy.

Most likely, both will coexist – handicrafts and niche workshops on one side, large-scale robotics in automotive, electronics, and medical devices on the other.

Economics and the tipping point

The assumption has long been that Indian labour is cheaper than robots. But collaborative robots today can cost $20,000 to $40,000, while a factory worker may cost $15,000 over five years.

One robot can replace multiple workers, operate continuously, and deliver higher productivity with fewer errors.

As robots get cheaper and wages rise, the economic argument for automation strengthens. The tipping point will come when SMEs, not just multinationals, see robots as the rational choice.

Think global, act local

The future of robotics in India will likely be defined by the competition between foreign OEMs and domestic builders. Foreign companies bring proven technology and global networks.

Domestic firms bring local knowledge, lower costs, and the ability to adapt machines for Indian realities.

GreyOrange shows that an Indian firm can go global in robotics. Addverb, Genrobotics, Sastra, and Planys prove that niche machines can scale. But whether India can produce dozens of globally competitive robotics firms – as China has done – remains to be seen.

If domestic firms succeed, India could become not just a consumer market for imported robots but a global exporter of robotic systems. If foreign firms dominate, India risks becoming merely a sales territory.

Either way, the next decade will be decisive. India has the population, industrial ambition, and momentum. Now it must decide whether its robotics future will be built at home, or bought from abroad.