A couple of days ago, we published a story about a humanoid robot learning to play the drums – not by being pre-programmed note for note, but by being trained to develop rhythmic skill over time.

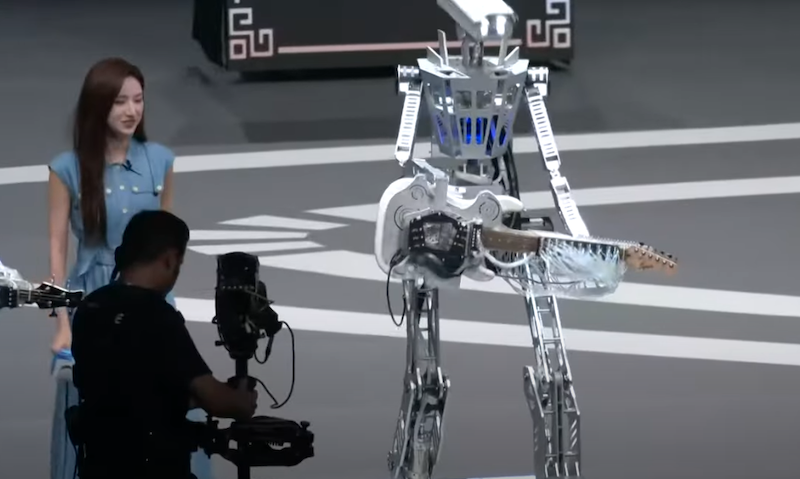

More recently, in another video making the rounds online, humanoid robots were seen playing guitars (main picture).

These performances are technically impressive, but they also hint at something more profound: the possibility of robots being used not to generate digital music, but to physically play real instruments.

For music lovers who appreciate the richness and authenticity of analog sound – the kind you get from live instruments recorded without digital shortcuts – this could be an appealing idea.

The enduring allure of analog sound

Vinyl records are not just a nostalgia trip. Their continued – and growing – popularity is evidence of a persistent desire for authentic, analog sound.

Vinyl’s revival in numbers

Technavio projects the vinyl record market will grow by $857 million between 2025 and 2029 at roughly 9.3 percent annual growth rate.

Global Growth Insights estimates the market was worth $1.53 billion in 2024, will rise to $1.63 billion in 2025, and could hit $2.83 billion by 2033.

In the United States, vinyl record sales overtook CDs in revenue in 2022 – the first time since the late 1980s.

Collectors and casual listeners alike cite a similar reason: vinyl just sounds more alive.

Analog vs digital – why it matters to discerning ears

You don’t need to be an audio engineer to notice the difference between an instrument played live and the same sound simulated on a keyboard or generated by a computer.

The science in simple terms

Analog recording captures sound as a continuous waveform – whether etched into a vinyl groove or magnetised onto tape. This mirrors the way sound exists in the real world and the way our ears perceive it.

Digital recording captures sound by taking rapid snapshots (samples) of that waveform, each represented as a number (bit depth). For CDs, this is 44,100 samples per second at 16-bit depth.

No matter how fine-grained the sampling, it’s still a series of discrete steps – just like a digital photograph is made up of pixels. Zoom in enough and you see the straight edges and squares; reality doesn’t have those, generally speaking.

Brian Eno, the producer and sonic experimenter, put it succinctly in Wired (2008): “In an age of digital perfectability, it takes quite a lot of courage to say, ‘Leave it alone’… The traces of human activity – brushstrokes, tuning drift, arrhythmia – are the fundamental texture of the work.”

In other words: digital can be perfectly clear, but it risks losing the micro-variations, flaws, and textures that make a performance human and emotionally engaging.

The limitations of loops and samples

Over the past few decades, digital tools have given musicians extraordinary creative freedom. Entire songs can be built from sampled loops, virtual instruments, and synthesized sounds.

Many are beautiful in their own right – but when a digital keyboard “plays” a guitar sound, it’s an approximation, not a vibration of real strings in air.

Even high-quality sampled instruments cannot replicate:

- The subtle interaction between a player’s touch and an instrument’s mechanics.

- The resonance of wood, metal, and air in a real space.

- The imperfections – timing variations, tonal quirks – that give character.

This is where robots could offer something genuinely new.

Robots as analog musicians

Humanoid and mechanical robots are already capable of playing drums, pianos, and string instruments with a level of precision that rivals the best human session players.

Why this matters for analog purists

If a robot plays a real instrument, you’re hearing real sound waves generated in real time — just as you would if a human played. The difference is that robots can:

- Perform with repeatable precision for multiple takes.

- Play complex arrangements beyond the physical limits of one person (think of Pat Metheny’s Orchestrion project, where mechanical instruments played entire orchestrations live).

- Allow composers to hear their work performed acoustically without hiring an entire ensemble.

For producers who care about authentic timbre but don’t have access to live musicians, this could be a bridge between convenience and analog truth.

A suggested analog-first workflow for musicians

If you want to keep the listening experience as rich and “real” as possible, here’s one way to do it:

- Compose digitally – Use a DAW to write, arrange, and notate your music. Treat the computer as a sketchpad, not the final medium.

- Program robotic performers – Translate MIDI or notation data into commands for robots that play real instruments: drums, bass, guitar, brass, strings.

- Record in analog – Use tape machines, tube preamps, and vintage microphones to capture the performance directly to an analog master.

- Minimal cleanup – If needed, use gentle analog-friendly noise reduction (e.g., SweetVinyl’s SugarCube, Pro-Ject’s NRS Box) to reduce crackle or hiss without stripping warmth.

- Master for vinyl – Keep the signal chain analog where possible before pressing to vinyl.

- Playback in analog – Let the listener hear the performance as a continuous waveform, unbroken by digital conversion.

This keeps digital in the early creative stages but ensures the actual sound capture and final delivery are in the analog domain.

Innovations keeping vinyl fresh

Vinyl isn’t static. Several recent advances help preserve its analog depth while reducing its traditional drawbacks:

- Pro-Ject Vinyl NRS Box S3 – Hardware that filters crackles and pops in real time.

- SugarCube SC-1 – Removes surface noise algorithmically, leaving music untouched.

- Improved pressing techniques – Modern manufacturing can reduce surface imperfections compared to mass-market 1970s to 80s vinyl.

These tools mean vinyl listening today can combine analog warmth with far cleaner playback than the format’s reputation might suggest.

What famous musicians have said

While few artists spoke publicly about the vinyl-to-CD shift at the time, some have voiced strong format preferences:

- Frank Zappa: embraced the digital Synclavier for composition but remained deeply involved in the mastering of his catalog, showing concern for sound integrity.

- Jack White: “I prefer vinyl … it’s a shame the new generation is missing out on albums.”

- Bob Pollard: “I don’t think it’s real unless you put it on an LP. CDs aren’t real. Anybody can do that.”

Even artists who use digital tools extensively often acknowledge that analog formats retain a sonic and emotional pull that digital hasn’t replaced.

A new frontier for analog sound

Robots playing real instruments could open a fresh chapter in music production. For those who value sound that’s as close as possible to the truth – with all its depth, warmth, and idiosyncrasies – this approach offers something exciting:

- The authenticity of analog sound waves generated in real space.

- The repeatable precision and flexibility of robotic performers.

- The tactile beauty of a vinyl record as the final product.

In an age where music can be created without a single vibrating string or drumhead, there’s something radical about returning to the physicality of sound – even if the hands on the instrument are made of metal.

Top robots that actually play real instruments

Compressorhead

A rock/metal robot band from Berlin, where each member is a robot constructed from recycled parts and controlled via MIDI sequencer. They play real guitars, bass, drums, and even include a vocalist.

Notable members include Fingers (78-fingered lead guitarist), Stickboy (four‑armed drummer), Bones (bassist), and vocalist Mega‑Wattson.

They’ve performed live – including festivals like Wireless – and even appeared in Travis Scott’s Circus Maximus film.

Haile (Georgia Tech Robot Percussionist)

Developed by Georgia Tech’s Gil Weinberg, Haile is designed to listen to live music and improvise by playing acoustic percussion in real time.

Its wooden form mimics human movements – striking the drum from rim to center – and translates musical cues into expressive drumming.

GuitarBot (LEMUR / Pat Metheny’s Orchestrion)

Created by LEMUR (League of Electronic Musical Urban Robots) in 2002, GuitarBot is a self‑playing guitar module, controllable via MIDI.

It was central to Pat Metheny’s Orchestrion project, bringing mechanically played acoustic instruments into live performances.

Cello-Playing Robotic Arms (Fredrik Gran)

Swedish composer Fredrik Gran repurposed industrial robotic arms – originally built for assembly lines – to play bowed instruments like cello and double bass.

The robots even prepare their bows and can tune instruments, performing duets with human programmers.

Beatbots (Robotic Percussion Quartet)

A 2025 academic project featuring four percussion robots – designed with direct musician feedback – to play complex rhythmic patterns with playfulness and physical engagement.

Audience studies revealed strong appreciation for their aesthetic and performative qualities, blending robot precision with expressive percussion.

Robot Drummer (SUPSI / Politecnico di Milano)

A humanoid robot capable of playing drums at up to 200 BPM with over 90 percent rhythmic accuracy, showing human-like nuances like stick switching and cross-arm hits.

Z‑Machines & Squarepusher

A Japanese trio of robots built to perform virtuosic compositions – creating the EP Music for Robots by Squarepusher.

The Trons (New Zealand)

A quirky self-playing robot band of four, made from scavenged parts, playing simple chords and rhythms through mechanical ingenuity.

ArcAttack

Performance group using a robot drum kit and singing Tesla coils controlled by MIDI – straddling the line between robot and instrument.