DNA Paints a Literal Picture of Your Face

Two women in their 70s were sexually assaulted and killed in 2006. Police found the DNA of a suspect at the crime scene, but without a person to link it to, what use is DNA?

Much more than most ever could have imagined, it turns out, thanks to the improving sciences of DNA phenotyping and genetic genealogy.

Virtually every physical attribute a human has – ancestry, skin color, eye color, freckles, dimples, face shape, and much more – is encoded in DNA.

But while in the past DNA was used to confirm a suspect’s guilt; DNA phenotyping and genetic genealogy are now helping predict what a suspect might look like. This is a huge leap forward, especially as it concerns “cold cases”.

And while there is some controversy – particularly related to Parabon Nanolabs, the main company currently involved with processing physical predictions based on DNA – these new tools are generating leads and even arrests.

Genetic genealogy is hardly a new scientific breakthrough. Even a home DNA test offers various information such as where your ancestors came from and how closely related you are to kin.

It’s only been in recent years, however, that such techniques have been applied to forensic science.

Here’s an attempt at a short explanatory story: Cops find a suspect’s DNA. But usually things don’t play out like an episode of CSI: input DNA, computer whirls and boom, busted.

What’s happening now involves investigators searching all public DNA databases – actually hoping to find someone related to the suspect. If they find a sibling, well, that’s an incredibly lucky break and not common.

But it doesn’t need to be as close as a sibling; the DNA of, say, a cousin; even a distant cousin could lead to a break. But people have a lot of cousins, close and distant.

Instead, if investigators can find two cousins who are not related to each other but are related to the suspect, they now have information on the paternal and maternal side of the suspect’s family.

If they see a cross-over point, which might be only one person or perhaps siblings, who are cousins to the unrelated cousins the field of possible suspects is drastically narrowed.

Increasingly being paired with genetic geology is DNA phenotyping. The main firm involved in that process is Parabon Nanolabs, which since 2015, claims that its technology has contributed to solving some 100 cases – including some “cold cases.”

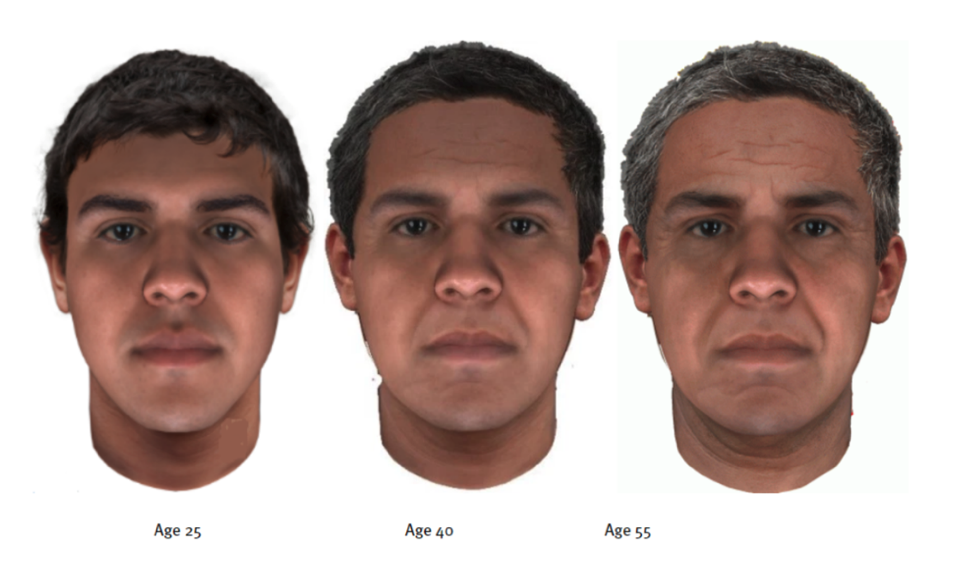

The killer of the two Virginia elderly women referenced at the beginning of the article has yet to be found, but courtesy of DNA phenotyping, there’s now a very decent chance he will be. In December 2019, police released a series of drawings that show a light-skinned male.

He is pictured at three approximate age ranges: about 25-years-old, around 40-years-old, and at 55. The information extracted from the suspect’s DNA was processed by Parabon Nanolabs, to create a “predictive picture” of the suspect.

Why the age ranges? Age is the one thing DNA can’t show.

A spokesperson for Parabon Nanolabs told local media that they aren’t producing a “photograph”.

“It never could be,” the spokesperson went on. “Because if that person went out and got a tattoo tomorrow, then what we produce will not look like them, or if they shave their head.” But having a realistic picture of what the wanted person very likely looks like, including race, face shape, eye and hair color, is invaluable to investigators.

Equally or even more important for a person innocently accused, DNA phenotyping can say with a supremely high degree of confidence what the suspect does not look like.

Dr. Ellen Greytak, who works for Parabon Nanolabs, pointed to a case in Louisiana in which investigators were looking for a Hispanic male suspect as the female victim’s phone records showed her only speaking with Hispanic males prior to her death.

But DNA phenotyping told police to look instead for a northern European male with blue eyes.

There are some concerns. Robert Perry, legislative director of the New York Civil Liberties Union in 2019 told the New York Times, “The problem is, its [DNA phenotyping] use will place actual people, innocent of wrongdoing, under criminal suspicion without any basis in fact or science.”

While the debate continues, proponents of new uses for DNA point to more than one successful case resolution, going back to a 2015 case in Maryland. In June of that year, a man died from complications resulting from being shot five years earlier.

The death was ruled a homicide. Parabon Nanolabs offered cops a “composite sketch” based on DNA. The suspect, the company claimed in December 2015, was male, had green or hazel eyes, brown or blonde hair, fair-colored skin and was of western or northern European decent.

Building on the phenotyping, in July 2018, Parabon Nanolabs shared a genealogy report that the company said showed ancestry lines.

Parabon Nanolabs said their evidence pointed to a Fred Lee Frampton, Jr Police followed the suspect, picked up a cup he threw away and tested his DNA against the DNA left at the crime scene five years ago. It matched. Frampton pleaded guilty and was sentenced to life in prison.

The fact that these new uses of DNA are controversial is a good thing. No one wants to get ahead of proven science, but as things stand right now, it seems highly likely that DNA phenotyping and genetic genealogy are set to become cornerstones of 21st century forensic science.