The Discovery: Postcards from the afterlife

Being from a pre-internet age, I find it surprising when an online company makes or at least funds a good movie, and The Discovery is a very good movie.

And it’s not just because Robert Redford stars in it that makes it look like a good movie, although that is definitely an advantage because he gives the film a sort of timeless quality and provides a link between an older generation who lived without many of the astounding technologies we know about and perhaps use today.

He’s also an appropriate casting selection for a Netflix movie because he’s a champion of independent films and founded the Sundance Film Festival. Not to mention the fact that he’s also been in some of the most memorable movies of all time, and some that are less well known but of a very high quality nonetheless.

The discovery which gives the film its name relates to Redford’s character’s discovery of not only the existence of an afterlife but also his invention of devices which can connect to the brain and project images from that afterlife onto a screen.

Amazing technologies like this may or may not exist in our real or simulated world, but there are scientists who claim that they have built instruments which can detect extremely faint electrical signals from dead bodies, and the more turbulent the circumstances of their death, the more strength those signals are said to have.

Whether these signals can be converted into pictures is a question which I think many scientists are probably working on answering.

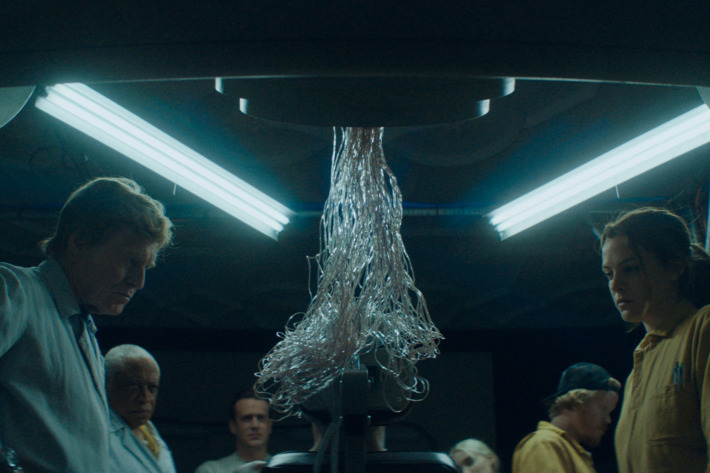

One of the contraptions shown in The Discovery – something which picks up signals from the brain – looked like devices already used in the medical sector, sometimes referred to as “brain-computer interfaces”.

There are many companies developing these devices to varying degrees of success.

One which was demonstrated to former US president, Barack Obama, was capable of picking up signals from a paraplegic man’s brain and manipulate a robotic arm accurately enough to pick up a cup of coffee.

That one, however, was invasive, meaning, a part of it was directly connected to his brain.

The devices shown in The Discovery tended to be non-invasive, and just worked by picking up signals on the surface of the skin, which is what some of the more recently developed brain-computer interfaces are attempting to do.

The film does go into some very serious issues relating to how such a profound discovery can change people’s attitude to life and death, and depicts a world where literally millions of people choose to die to “get there” to the afterlife.

While, of course, The Discovery is science fiction, it’s a damning indictment of contemporary society, where suicide rates in the US and several other countries are higher than they have ever been.

For most of us, it may be difficult to imagine wanting to die to “get there” and see the afterlife, especially when the technology in the film enables you to see it while you’re still alive. But it’s probably easier to understand in the context, as hinted at in the film, where people’s lives are miserable and totally controlled.

As Redford says at the beginning of the film, “There’s nothing willy-nilly.”

He was talking about having made the discovery public, for which he was being vilified because it supposedly led to people wanting to commit suicide. Apparently, judging from the question asked by the journalist who was interviewing the Redford character, some people thought the discovery was “too dangerous to share with the world”.

Typical “shoot the messenger” diversion from the real problems and issues, which must address questions relating to who controls the technology and how it is being used. In that sense, the film was quite realistic.

Anyway, his answer was: “After much discussion, much debate, we all came to the same conclusion, which is, once you explore all scientific possibilities and you come to a consensus, how can you keep a discovery so vital to our existence a secret?”

The machine Redford’s character builds is capable of capturing “brain wavelengths on a sub-atomic level leaving the body after death”.

Why this discovery would lead to millions of people wanting to die is a bit beyond me. What would worry me more is scientists like Redford’s character capturing brain wavelengths leaving the body while people are still alive and going about their daily lives without any idea that someone somewhere is stealing eavesdropping on their thoughts.

It’s only possible to address one or two issues at a time adequately in a film, and it my ideas about stealing the essence of living people’s brains while it’s still in their heads and their sovereign territory are probably passé, so adding to what The Discovery was already dealing with would probably made it too convoluted.

And the film did deal with its chosen subjects very skilfully, and even managed to weave in subplots about love and loss, as well as the concept of a simulated universe on an infinite loop through a plot device similar to that shown in Groundhog Day.

Clearly, filmmakers think of dystopia as a world where the controllers want everything to happen the same things to happen to the same people, in the same way, every day forever so they all they have to do is refine the details rather than have to deal with freedom with all its unpredictable dangers. Loops probably save a lot of computing resources or something.

I’m probably giving too much away here, or not enough – who knows? – but The Discovery was one of the highest-grossing movies of 2017 so it’s likely that you’ve already seen it.

Strangely enough, what I found most unrealistic about the movie is the scenes where there was some peace and quiet, with the Jason Segel character even remarking, “I thought I was alone”, while travelling on what seemed like a public transport boat.

Who on Earth – literally the whole of the Earth – is alone these days? Even in space, someone can hear you scream.

Plus, there was only one other person on the boat – the Rooney Mara character, who says several times in the movie that she doesn’t feel any emotions, which is a much more authentic reflection of the modern human condition than empty boats and sparsely populated roads and the absence of disruptive noises and people engaging in directed conversation.

It’s not the first time I’ve noticed that films and television shows have shown scenes – perhaps of streets or some other setting – where the characters are not only ignored or left alone by passers-by, there are actually no passers-by. How realistic is that? Is that some sort of aspirational image filmmakers utilise to fill us with a sense of awe at the mere thought of some solitude and enough privacy to live what used to be called a normal life?

That type of picture or scenario seems to have become a template and it’s made me curious about whether or not filmmakers are making a pointed comment about today’s society.

I could be totally missing the point and it could actually be that they simply streamlined the budget and decided not to employ any extras.

Segel actually has more screen time than anyone else in The Discovery, and is given some of the best lines, calling the group of people who have gathered around Redford character a “cult” and playing the average guy who finds himself struggling to cope with what’s going on. “I’m just … processing,” he says at one stage, making me wonder how much computer memory one would need to process, store and analyse a person’s thoughts.

I thought The Discovery was the best film I’ve seen made by Netflix or any of the online movie companies, Amazon Prime included. Especially Amazon Prime included.

And if they do keep producing them at that sort of quality, there really will be fewer people on the streets and on public transport. But that doesn’t mean you’ll ever be alone. Not even in death, if films like The Discovery and Hidden Reserves are anything to go by.